By Lynn Sygiel, editor, Charitable Advisors

A little over a year ago, Mike Chapuran’s first day at Family Promise in the Martindale-Brightwood neighborhood didn’t go quite as planned.

Trying to get a sense of his new position, he started his first day answering the nonprofit’s phones. The first caller was a family, which he had to turn away because the shelter was full. Then came another call, and by 9:40 a.m., he had turned away five families seeking shelter.

Twelve minutes later, he suggested the caller call 211 or one of the other two family shelters – Dayspring or Holy Family.

“The mom told me, ‘I’ve already called all of them, I’ve been calling them for weeks. I’m staying in an attic and it’s 80 degrees and my infant won’t stop crying. Do you know how hot it gets in an attic?’ I felt powerless, but imagine her powerlessness. I’m just in a job. She’s has a kid. My point is on the day I arrived here, I was like ‘I didn’t know this was a problem in Indianapolis.’”

Unfortunately, Chapuran’s first day was not unusual. Every day, about 10 families are turned away. Other family shelters in Central Indiana – Dayspring and Holy Family — have similar experiences. According to Coalition for Homelessness Intervention & Prevention (CHIP), 6,000 school-aged children will experience housing instability. Dayspring, Holy Family and Family Promise will take dads, but Salvation Army and Wheeler only take mothers and children.

For over 24 years, Family Promise of Greater Indianapolis, initially called the Interfaith Hospitality Network, has been part of the network supporting homeless families. It began with a talk given at St. Elizabeth Ann Seton Catholic Church by the founder of a Hospitality Network program in New Jersey. Dr. Dean Lindsey was at the talk, researched the program and problem, and then formed a local outreach group to connect with congregations. Working as volunteers, they persuaded eight congregations to split the effort that first year, each hosting four families for a week.

Since 1994, volunteers and congregations have helped over 750 families with children. Today, two different congregations offer hospitality every week, serving a total of eight families. The network now includes 36 churches, and another 18 that support the effort of a church close to them.

Congregations provide overnight lodging and meals for up to four families. Families daily arrive daily at the church at 6 p.m. and stay until 7 the next morning. On Sundays, volunteers wash sheets, and then transport the rollaway beds to the next congregation.

“If a parent has a job and works until 6, we don’t want to be an obstacle to employment so we have the Uber and Lyft fund. We will have volunteers go pick them up for the week. We don’t let our model get in the way of what actually matters, which is working,” said Chapuran.

Host congregations serve dinner and breakfast and plan activities for the children. Members of the congregation spend the night at the shelter, and then each morning transport families to the Family Promise Day Center. Children go to school or daycare.

The Day Center, located behind St. Rita’s Church on Indy’s Eastside, provides support for adults who either cannot work or are seeking work. They meet with a case manager to build skills such as budgeting, while applying for housing or employment. Adults can use the computer lab to prepare resumes, research jobs and apply for jobs online.

“We have success stories. We have the mom who comes back seven years later, and we don’t know she stayed in the program. She’s wearing nursing scrubs, and she donates food to us and says, ‘Seven years ago this program saved my life.’ She then talks about the volunteers and how they doted on her children and how she got a job as a CNA at $15 an hour and the program helped her get that. And that now she’s has an apartment.

“We have another mom who says after she puts her kids to bed and turns off the lights, she loves it because she has to get mad at her daughter for turning on the lights and reading a book at 9 o’clock at night,” he said.

When a family leaves, support continues. Four years ago, the program added an AfterCare home-based case manager who continues to work with families. The belief is that INH helps people find housing and AfterCare helps them keep it. The nonprofit’s name was changed when it added the program, and is now part of an affiliate network of over 200 Family Promise branches.

The case manager visits families at their houses or apartments, and currently serves 32 families.

“That’s scary because that’s a lot. So she has to prioritize those most in need. Families will do a monthly budget with her one meeting, and then next month when she’s back, revisit it. There may be a meeting in between to work on things like providing a connection for a school uniform resource. But it’s really budgeting on the first of the month, and then coming back the next month to try to help create long-term goals as motivation,” said the executive director.

And it is making a difference. Two years after leaving the IHN shelter program and working with AfterCare case manager, 82 percent of families have retained housing.

In the past year, the case manager has connected six families to the Boner Center IDA program. The family starts an account and saves a minimum of $25 a month. When they hit $3,000, it’s matched and can be used for school, entrepreneurship or buying a home, according to Chapuran.

“So we’re hoping that through that program we’ll have some homeowners here in a few years,” he said. “Housing is the key. There’s no panacea. Right? But housing affects employment, affects school, affects every thing.”

Most families, according to Family Promise, stay about 60 days to save up the first month’s rent and security deposit. The nonprofit now has a donor to provide a family’s security deposit, which according to studies, reduces the average family stay.

“We just gave a fighting chance to the family. The family did the work. It’s not a homeless person, it’s a mom who has three kids. One of them was diagnosed on the autism spectrum, she had to do appointments, lost her job and then it snowballed from there. It could happen to anybody,” said Chapuran. “We can stabilize those parents so that the kids’ lives hopefully are stable and in school. So we’ve got to take the long view.

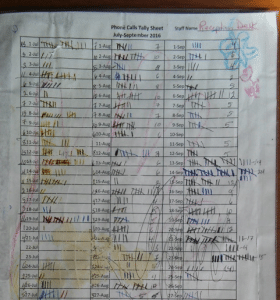

Family Promise of Greater Indianapolis phone tally for two months.

Permanent housing for families, particularly with multiple bedrooms, is rare to find.

“Your family of five with dad, mom and three kids is shot. They wait. We’ve had a family that’s come back here twice despite our best efforts and getting social security and some other supports, and despite a part-time job has come back here twice. The mom has significant disabilities, retaining a job is hard. She’s half blind to be honest, and a permanent support-housing unit is necessary for her and her twins. But she’s been waiting nine months now.”

Besides family permanent housing, Family Promise is working to fill a 17-week gap from December to February. At that time, one rotation serving four families at a time closes. The nonprofit continues to recruit congregations.

Chapuran is hopeful that he will find new congregations and maximize the nonprofit’s existing resources.

But most importantly, he knows that volunteers getting to learn a family’s story can realize that it’s all shared experiences.

“Read the stories, but even more important than serving a meal at Dayspring, is talking to a family at Dayspring, learning a story. Learn that’s a mom, who went through 24-hour childbirth just like you, who then was worried about getting the baby to latch. It’s all shared experiences. “