By Lynn Sygiel, editor, Charitable Advisors

In Indiana, the month of March is filled with basketball, and if that madness doesn’t grab you, then just wait till May when the roar of the crowds turns into the roar of the engines. Hoosiers, like people all over the country, love a bit of competition. But not all of it takes place on the playing field, and not every competition ends up with someone holding a trophy.

That’s not to say there aren’t winners, especially in the world of nonprofits, which have adopted the concept as they attempt to expand their presence and draw attention to their work.

The Chicago-based MacArthur Foundation has an admirable mission: “To support creative people, effective institutions and influential networks and build a more just, verdant and peaceful world.” In order to discover those elements, the foundation launched a $100 million grant competition in 2016. It was looking for a single proposal to solve a critical problem affecting people, places or the planet. Called 100&Change, it was open to organizations working in any field of endeavor anywhere. After reviewing 1,904 proposals, it named its recipient in 2017 — Sesame Workshop and International Rescue Committee.

While competitions in general are not new, what is new is nonprofits turning to these challenges to drive innovation. Increasingly, they are discovering that many of the very best ideas lie outside their organizations.

This is true for Early Learning Indiana (ELI). Not only was its recent statewide Child Care Desert competition designed to spur innovation, but there was another motivation – it was a way to expand early learning seats in Indiana, said President and CEO Maureen Weber.

“As an organization, we are really focused on bringing together sort of a system of stakeholders to create accessible, high-quality early education opportunities. We absolutely know that we cannot do this on our own, not on our own in Central Indiana, and not on our own across the state. We needed a way of bringing others into the fold. We felt as though we were having conversations with the same sets of people,” said Weber, who has been in the role for two years.

The light bulb went on for ELI in 2014, when it changed its mission and name, its leadership team and board wanted to do more to expand access and quality early childhood education across the state. They knew that crucial brain development occurs during those early years and can provide a foundation for success in school and beyond. They also knew that early education could have a positive ripple effect that extends to their families, communities and the economy.

The mission gained steam in that same year, ELI approached Lilly Endowment and was awarded a $20 million grant to launch the Partnerships for Early Learners. The initiative was to increase access and quality of early childhood programming across Indiana. ELI now not only had a goal but the funding to pursue it. The next step was to invite potential partners to the table, discover what needs were out there and attempt to fill them.

Andrew Perrin, ELI’s board chair and PNC’s senior vice president and regional sales executive joined the board in 2014.

“My take was the headwinds to getting early childhood education to where it should be were so big that the status quo clearly wasn’t going to cut it. I welcomed any innovation in the space. So, the idea of having a competition, maybe there are other avenues to do it, but I loved the energy of something fresh,” said Perrin.

“I think what makes ELI uniquely positioned is at our core we are a provider of early childhood education. It gives us a level of expertise, as well as, appreciation for what the challenges are. I think that core helps inform our partnerships and advocacy for expanding both quality and accessibility.”

The Partnership for Early Learners initiative added a new role for ELI. It has received and granted over 55 grants to help other providers in the state build their capacity. Early in the effort, Weber said, providers needed funds to meet either licensing or quality requirements. Funds from the grant also helped 400 early childhood educators earn new degrees or credentials.

“Maybe they were lacking a scald valve on their sink or early learning curriculum. So, that was something we could help them invest in and then they could meet the standards and then they could serve children,” said Weber. “We had to get more creative in how we thought about the work, so that the amounts of the work got bigger as well because there were just bigger gaps to close.”

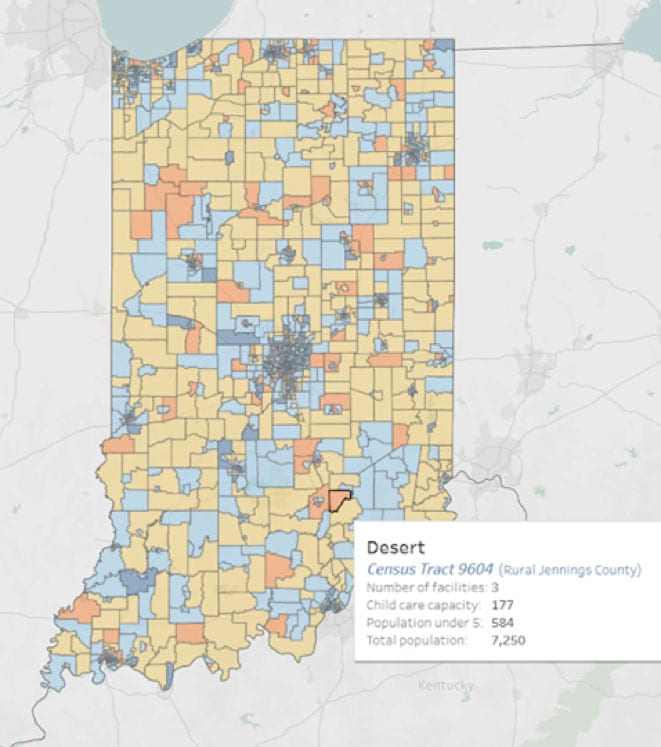

Lack of access, however, continues to prevent many Hoosier children from receiving the benefits of an enriching early learning experience. In 2018, in tandem with Indiana Business Research Center (IBRC), ELI studied access, capacity and need and found that in Indiana, 45.2 percent of children live in a child care desert. ELI defines child care deserts as places with no more than one child care seat for every three children. This study also helped illustrate and raise visibility.

“I think the research, especially in a fiscally conservative state like Indiana, built a business case for early childhood care and education. Anytime you can measure something, it gives people more assurance that this is an effort worth buying into and joining. So, I think what the desert study did was is say, ‘Hey, look, here is the gap,’” said Perrin.

When ELI launched its Child Care Deserts competition last summer, its goal was to address these critical care shortages around the state. Unlike many competitions, ELI offered webinars to ensure applicants understood the data to better incorporate it into proposals. Weber said ELI also shared with potential awardees what is a high-quality seat and the long-term impact of having those available.

“We started this effort by surveying the national landscape and getting a really good sense of what ‘good looks like,’” said Weber. “We wanted to bring those best practices as food for thought to the communities that were applying, while understanding unique community needs. So, part of our education process was to share some great things we’ve seen done across the country. But we also had to understand the unique needs of each community with whom we were working.”

“We spent a lot of time helping our audience prepare their applications, and so we hosted webinars, we had self-service data opportunities so they could know ‘Here’s what the state of the state in our community looks like,’ and had people on tap to sort of help walk through those questions as they had them,” said Weber. “The award itself had to go to a nonprofit, but we encouraged really diverse partnerships. That’s what we had in most places,” said Weber.

Having funding available and the Child Care Deserts study provided an opportunity to have a conversation with a business audience, too, said Weber.

Purposely, there were two phases to the challenge. The first was a letter of intent. From that pool, ELI narrowed the pool to 19, which gave time for those communities to formulate plans and build local partnerships before submitting final proposals. In January, ELI awarded $1.4 million to 13 organizations that will add nearly 1,000 high-quality seats for child care across the state by the end of the year.

Montgomery County Community Foundation was one of the awardees. Although they have many other partners, the funds had to be awarded to a nonprofit. The IBRC study ranked the county among the 10 lowest for child care seats, with only 2 percent of the county’s children under the age of 5 enrolled in high-quality programs. The $100,000 grant will help two local providers add 80 seats by the end of the year.

But that’s not all the grant competition did. Not only will it increase availability in these 13 communities, it elevated the conversations in the community.

As the Montgomery County Community Foundation’s executive director, Kelly Taylor had seen an uptick for early learning and child care grant requests over the past five years. In fact, the foundation had granted nearly $150,000 to child care nonprofits. She said the child care deserts’ study only confirmed what they were hearing. But the competition coalesced the community’s efforts.

“I think what we saw come out of this competition in our community was it rallied diverse groups to work together. We wanted to represent our community well and increase the number of child care seats and have them be of quality level. It really spurred people to action,” Taylor said.

“We know there is still a lot of work to be done, but we think having that success brought a lot of attention to the value of early learning throughout our whole community. We could not have done it on our own. We were able to talk about that data and about what this $100,000 award will do in our community. That has really captured the attention of people in our community and will help us to again continue to move forward,” said Taylor. “We had this early success and we want to build on this. I think it keeps the momentum moving forward.”

Currently, the community is formalizing its Early Childhood Coalition. As part of this effort, it reached out to seven corporate organizations that have provided financial support for the efforts. Part of the plan is to start a resource fund to help providers with training and credentials. In addition, the community foundation and city came together to understand the issue in their community. They engaged a local consulting company to do a community-wide needs assessment. Through surveys, focus groups and a bus tour of existing child care facilities, they understood what is being offered. They did video conferences with other Indiana coalitions to learn what was working.

“We started in August and finished our strategic plan in January. We were meeting constantly during that time, gathering data, analyzing data and putting together a five-year strategic plan. We have a plan to move forward now and really focus on this issue in our community,” said Taylor.

Weber has seen other changes, too.

“When I started in this role nearly two years ago, we were still having conversations about ‘Why this matters. What’s the value? What’s the importance for economic development?’ I have very few of those conversations any more. It’s much more a conversation about what do we do to address the fundamentals. How can we help?” said Weber.

“What we were trying to do was to really elevate the conversation and get people talking from a variety of different perspectives. I really felt like we did broaden the top of the funnel in the number of people that we are reaching,” she said.