Local experts say transformative change demands a comprehensive strategy

by Shari Finnell, editor and writer, Not for Profit News

With the events of 2020 heightening awareness around the need for racial equity and social justice reform, nonprofit organizations have been at the forefront of efforts to institute transformative change.

Yet, no matter how much progress was made in 2020, achieving racial equity in the workplace will continue to be one of the most important issues organizations must tackle for at least the next decade, predicted Ben Hecht, the CEO of Living Cities, a collaborative of foundations and financial institutions, in a Harvard Business Review article.

The work toward racial equity must be comprehensive and deliberate, according to two local experts who are immersed in racial equity initiatives.

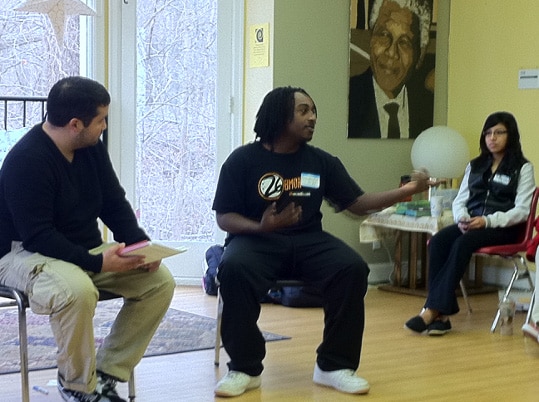

“It’s important for organizations to do an assessment of all their systems, including policies and procedures, how you recruit and hire, how you promote, and what ongoing training looks like,” said Tim Nation, executive director of the Peace Learning Center, which works with schools and organizations on educational initiatives around equity, social and emotional learning and restorative practices. “Not-for-profit organizations also need to assess how connected we are to the community. Do we act as saviors who know all the answers? Or are we really connected to the community in a way that we’re able to truly understand what their needs are?”

Nation also said it’s important to determine if the composition of the organization’s board and staff is representative of the communities they serve.

The Peace Learning Center, which has been at the forefront of racial equity initiatives since its inception in 1997, continues to assess itself against those measures. “We have, at the Peace Learning Center, established a racial equity committee that is assessing where we are on all of those different components — determining our strengths and weaknesses, and identifying areas that we can improve.”

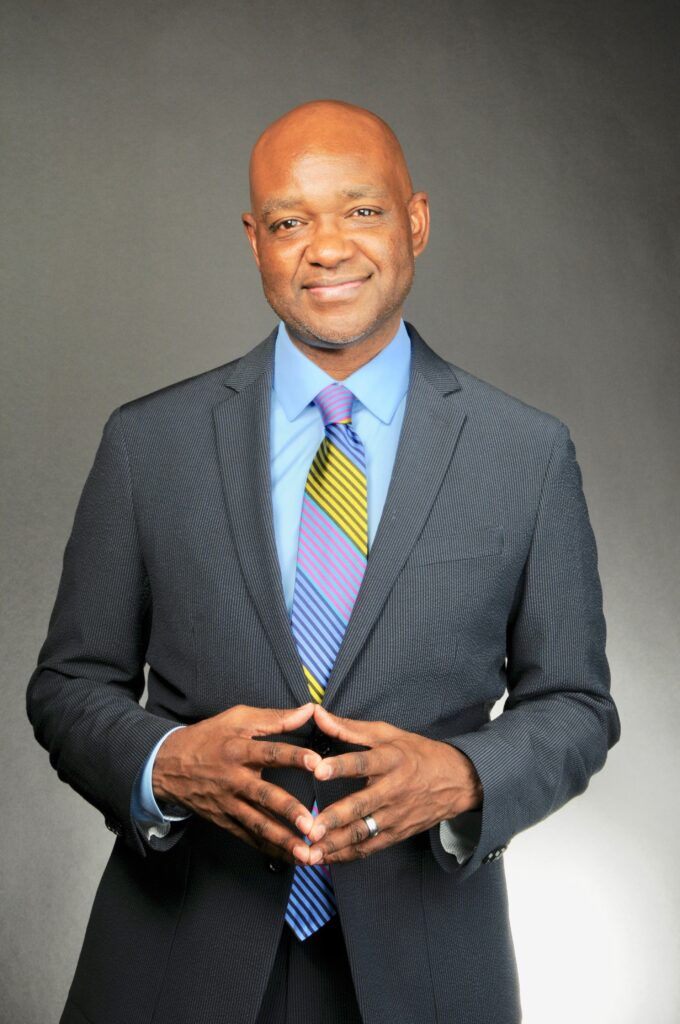

Michael Twyman, principal/owner of InExcelsis, a consulting firm, said the work to achieve racial equity within the workplace can seem daunting but nonprofits and other organizations must commit to it as they would with any other major initiative.

“It’s a lot of work, but it’s necessary work,” said Twyman, who also is an associate faculty member of the IU Lilly Family School of Philanthropy. “If we’re willing to do the work for other initiatives because we believe they’re important, we must put forward the resources to make racial equity happen.”

“We have resources at our disposal. How we deploy them or allocate them is a matter of choice,” Twyman added. “It can be something as simple as shifting the mindset. Most organizations will need professional assistance.”

Nation said anti-racism training is only the start in achieving substantive change. “When it comes to racial equity, the first step is awareness. You have to be aware of the issues and appreciate why it matters. A lot of training programs serve that purpose.”

All of Peace Learning Center’s staff members recently underwent training with Crossroads Against Racism in Chicago, which involved a rubric on how to become an anti-racist organization. “It identified where you’re at and what you need to work on,” said Nation, noting that the team followed up by reviewing all of its policies and recruitment practices.

Nation also said that people, particularly non-minority individuals, need to understand how deeply rooted racism is in American society. “It’s not as much as individual racism as it is institutional racism. An individual may not consider themselves as prejudiced, but the systems they work in, the history of racism in our country, which goes all the way back to slavery, have shaped the way institutions operate, including our government and organizations.

To illustrate the complexities of addressing racial inequities, Nation used an analogy involving fish. “If you go to a lake and see a dead fish, you say what’s wrong with the fish and you start trying to figure out how to fix the fish instead of addressing what’s wrong with the lake — the groundwater,” he said. “In the same way, we have a lot of initiatives to fix fish but we haven’t been getting down to the policies that created the problems.”

Educational systems, for instance, have devoted a lot of time trying to fix children instead of assessing the problems with the systems they must function in, Nation said.

The disparities between minority and white populations, including wealth gap and school suspensions, are examples of institutional racism at work, Nation said. Even with infant mortality rates, the richest black women have the same negative outcomes as poor white women, he pointed out.

“It’s racism,” Nation said. “All the evidence is there. Unfortunately, since it seems white people benefit from racism, some of them don’t want the system to change. There’s not a consciousness of how a changed system can benefit them.”

He also said that people often are confused about the definition of racial equity. “Equal is not always equitable,” Nation said. “When you have had 400 years of oppression for black people, it’s not difficult to understand why there is a wealth gap. It’s like a game of Monopoly. If you’re starting the game after all the properties have hotels on them, how in the heck are you supposed to catch up?”

Twyman, who has consulted organizations through diversity, equity and inclusion work, said that each organization must develop a customized approach to addressing those issues.

“If you’re serious about it, it really is a comprehensive approach to working and operating in a different way,” Twyman said. “It can’t be limited to ‘Sign me up for the workshop, check my name off the list and I’m good.’ We need to gain a deep understanding of the larger historical context that got us to the place where we are. There needs to be an acknowledgement of who we are as a nation. How it has brought us to where we are.”

Next, Twyman said, an organization needs to establish a mutually agreed upon definition of the terms racial equity and racial justice — the ultimate goal of what an organization will look like as it embraces those qualities. “How do you want to be operating differently?” he asked.

Lastly, an organization must work to define the journey, Twyman said. “How do those two things intersect — where your organization is now — the historical context, and the aspirational goal. What is the journey in between?” Twyman said. “How do you come together as part of a journey that takes you to a place where you’re no longer complicit and you’re advocating for racial justice? That can look different for every organization.”

The process can be challenging because it may require putting the organization under a microscope, Twyman said. “There has to be a sense of humility about accepting the possibility that we don’t know it all and that we unintentionally have been complicit in creating inequities, as well as helping to perpetuate them,” he said. “There also should be a willingness to hear the voices of people who have had the experience of being marginalized or oppressed … listening and accepting that at face value.”

The process could include a mix of ongoing professional development, training that focuses on changing organization culture, addressing the composition of the board and staff, and assessing policies, processes and procedures that unintentionally or intentionally serve to put people of color at a disadvantage, Twyman said.

Any assessment must be specific about issues around equity, sometimes in ways that may not immediately be obvious, Twyman said. For example, he said, a well meaning initiative to invest $5 million in a neighborhood to benefit minorities could have the opposite effect — gentrifying a neighborhood that, in the long run, doesn’t benefit them.

With nonprofits, businesses and other organizations putting in the work to achieve racial equity on a consistent basis, Twyman said, real change is possible.

“I am hopeful,” Twyman said.

“I think the promise of every new generation is that it will be a little smarter, a little wiser. Those who have joined and supported movements like Black Lives Matter are raising the questions around racial justice and demanding changes in a way that I haven’t seen in my lifetime. There’s urgency, clarity and energy,” he said. “Not to say that it didn’t happen previously. Now, it’s a broader and a more diverse movement that makes me very hopeful because I think that’s what it’s going to take.”

In the past, “We’ve all put this onus on people of color to fix this thing,” Twyman said. “As Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., said, ‘ We know through painful experience that freedom is never voluntarily given by the oppressor; it must be demanded by the oppressed.’ White people also have to demand change and be committed to the work that goes along with it.”